Each submission gets timestamped with EST time and gets a unique identifier

assigned, example:

S10056

Story by: Wandile Mthiyane

Wandile Mthiyane is an Obama Leader, TedxFellow, architectural designer, social entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Ubuntu Design Group (UDG), an architectural organization that focuses on social impact design projects ranging from individual housing to urban design scale.

In my second year of architectural studies at a university in Michigan, I was introduced to the “history of architecture.” As a South African, I was particularly excited about this course because the syllabus revealed that it covered African architecture. When the class began, we were briefly taught about ancient Egyptian architecture stretching from the first known architect who designed the pyramid of Saqqara to how great Egyptian ingenuity laid the foundation for the classical architectural language of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Learning that early inventions in African architecture shaped western architecture was revolutionary, but my excitement was short-lived as after only 14 pages into Egyptian architecture, we went on to study 576 pages of western architecture with slivers of Islamic architecture.

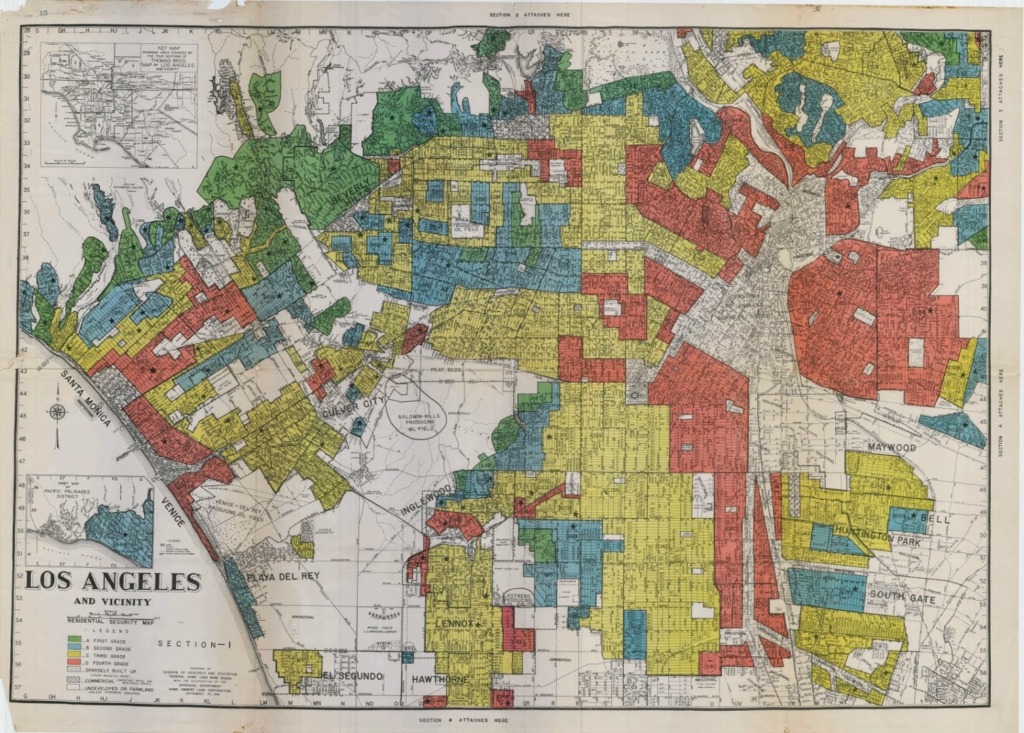

In light of the recent protest against police brutality and the continued work of the Black Lives Matter movement, it’s important for us as architects to take responsibility for the fact that design has historically been one of the most powerful tools to perpetuate systemic racism. Architecture is at the root of racial bias against people of color in America and around the world. Although informal discrimination and segregation has always existed in the United States, in 1934, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) instituted the National Housing Act that began the discriminatory practice called redlining.

Redlining is an unethical practice that places services (financial and otherwise) out of reach for residents of certain areas based on race or ethnicity. It can be seen in the systematic denial of mortgages, insurance, loans, and other financial services based on location (and that area’s default history) rather than an individual’s qualifications and creditworthiness.

This resulted in the dividing of neighborhoods along racial lines, leading banks to start lending to certain neighborhoods and not other neighborhoods based on race. The zoning laws and lending legislation at the time institutionally crippled predominantly African American neighborhoods, all the while lending to white neighborhoods, therefore enabling wealth accumulation.

The effects of redlining is evident in neighborhoods such as the one that former First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama, South Side of Chicago, which was stripped from economic opportunities. Property values went down the drain, which led to higher unemployment rates, which is associated with a desperation for survival and higher crime rates. Not every student was as privileged to afford the opportunity to take two buses 12 blocks away to attend Whitney M. Young Magnet school located on the westside of Chicago like the former First Lady was.

Most of the other schools nearer to the neighborhood were under-resourced which led to high dropout rates. This led to high unemployment levels and higher crime rates which the government used to justify higher police presence in the neighborhoods. Unfortunately, in America this directly relates to the higher numbers of deaths of innocent young Black men and women by the hands of the police. Thirty-eight years after Michelle Obama’s high school days, not a lot has changed. According to data from the Chicago Police Department, police are 14 times more likely to use force against young Black men than their white counterparts.

Like redlining and other government-sanctioned efforts to disenfranchise Black communities, the apartheid regime designed working camps known as “townships.” They used a system called the 40-40-40 rule where they built 40 square meter homes, located 40km away from economic centers. This forced Black people living in these communities to spend 40 percent of their income commuting to work, which rendered them incapable of developing their own homes. The communities were designed to be devoid of social and economic opportunities that crippled the Black communities’ economy.

Although Apartheid ended over two decades ago, township residents still commute 40km to work in town, limiting these residents to the same impoverished conditions into which they were forced during Apartheid. The laws may have changed, but the systems remain. Until we change the way we design and build, we’ll not be able to extinguish the evils of systemic racism.

According to a study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, three out of four neighborhoods that were redlined on government maps 80 years ago continue to struggle economically. We as architects are not just the designers of glass skyscrapers and infinity pools, but are direct contributors to these injustices. As Winston Churchill best put it, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

Ubuntu Architecture Summer Abroad Program has created a cross-cultural design-build experience for architecture students from around the world. This program is an intercollegiate educational experience in which students learn a community-centered approach to architecture. Students will design and build dignified and culturally-influenced homes for marginalized families in Durban, South Africa, who were affected by apartheid architecture.

The experience will aim to expose students to design problems stemming from systemic racism in a place beyond their own contexts. As apartheid architecture was used to segregate and oppress, community-centered design will focus on bringing people together and enabling equitable opportunities for all. At the end of the program, participants will be equipped with the tools necessary to implement change in their own communities.

As architects, it is important, and in fact we are trained, to take into consideration the entire environment into which we are designing. Examining existing architecture in the area, accessibility, the path of the sun, the approach to the space, and of course, climate and area become second nature to us very quickly. What we need to also make second nature in our designing and planning is examining the history of a place, the people of a place, and the culture of a place–for everyone.

Ubuntu Architecture Summer Abroad Program does exactly that: It trains the next generation of architects to take a broader view of the impact of their work and consider it more than just creating beautiful functional spaces; it trains us to see, hear, think, and feel beyond the aesthetics and into the community in which it resides.

Join us as we use architecture to begin the process of healing communities. Apply here: https://ubuntuasa.org/

Program Location: Durban, South Africa

Program Duration: May 15 – 29, 2021 (not including travel dates)

Eligibility: Third year to graduate-level architecture (and related) students

Each submission gets timestamped with EST time and gets a unique identifier

assigned, example:

S10056

Your ID: S12312312

This notification means your entry was sent successfully to the system for review and processing.

If you have any further questions or comments, reach out to us via the main contact form on the site

Have a great day!

New to NOMA?

Create your account

Already have an account?

Sign in

Not A NOMA Member? Click Here!

Create your account